Providing open access to scientific publications is a long-standing problem and new developments are on the horizon. Last year, the U.S. federal government’s Office of Science and Technology Policy required that beginning in 2026, publishers provide open access to publications originating from federal funding. This gives more momentum to the open access movement in academia.

At the same time, other trends are changing academic publishing, including the consolidation of journal titles and the provision of access by charging publication fees to authors (and their home institutions). In response to these developments, a group of MIT researchers is publishing a new white paper on open access academic publishing. The document brings together information, identifies outstanding questions and calls for additional research and data to inform policy on the topic.

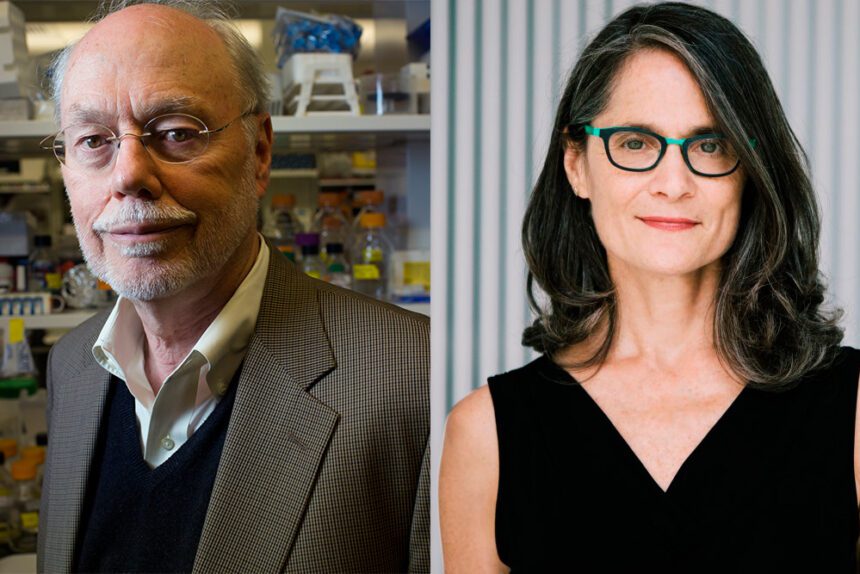

The group was chaired by the Institute’s professor emeritus Phillip A. Sharp, of the Department of Biology and the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, who co-authored the report with William B. Bonvillian, senior director of special projects at MIT Open Learning; Robert Desimone, director of the McGovern Institute for Brain Research; Barbara Imperiali, biology professor from the class of 1922; David R. Karger, professor of electrical engineering; Clapperton Chakanetsa Mavhunga, professor of science, technology and society; Amy Brand, director and publisher of MIT Press; Nick Lindsay, director of journals and open access at MIT Press; and Michael Stebbins of Science Advisors, LLC.

MIT News spoke with Sharp and Brand about the state of open access publishing.

Question : What are the main advantages of open access, in your opinion?

Amy brand: As the leading academic publisher MIT Press, we have long embraced open access to books and journals because our mission is to support our authors and disseminate their research to the world. Whether it’s removing barriers and paywalls altogether, or keeping prices low, we do everything we can to deliver the content we publish. Even before we were talking about federal policies, this was a priority at MIT Press.

Philip Sharp: As a scientist, I want my research to have the greatest possible impact, in order to help solve some of society’s challenges. And open access, which makes research accessible to people around the world, is an important aspect of this. But the quality of research depends on peer review. So I think open access policies need to be considered and promoted in the context of a very valuable and vigorous, peer-reviewed publication process.

Question : What are the key elements of this report?

Brand: The first part of the report is a history of open access and the second part is a list of questions that lead to evidence-based policy. On the one hand, questions arise such as: What is the impact of policies on the daily work of researchers and their students? What are the impacts on the laboratory? Other questions concern impacts on the publishing industry. One of the reasons I got involved in this effort is concern about the impact on nonprofit publishers, university presses, and scientific societies that publish. Some of the questions we raise relate to understanding the impact on small nonprofit publishers and, ultimately, how to protect their viability.

Sharp: Current open access policies being required by OSTP Nelson Memo radically change who pays for publication, where the resources for publication come from. There is a lot of emphasis on the research institute or other sources to cover this. And that raises another issue when it comes to open access: Will it limit publications by researchers at institutes that can’t afford those fees? The scientific community is very international and the impact of science in many countries is extremely significant. Managing the (impact) of open access is therefore something that needs to be developed based on evidence and policy.

The report notes that if open access were covered by one institution for all publications at $3,000 per article, the total cost to MIT would be $25 million per year. This is going to be a challenge. And if it’s a challenge for MIT, it’s going to be a huge challenge in a number of other places.

Question : What are some additional points regarding open access that we should keep in mind?

Brand: The Nelson Memo also provides that self-archiving is one of the ways to comply with the policy, meaning that authors can take an earlier version of an article and place it in an institutional repository. Here at MIT we have the DSpace repository which contains numerous articles published by professors. The economics are very different, and it is also unclear how this will play out. We recently saw a scientific society decide to implement a tax on this, something the community has never seen before.

But since we essentially have a system that already incentivizes publishers to increase article processing fees, publication fees, many questions arise about how publishers who perform high-quality peer reviews will be supported and where this money will go. came from.

Sharp: When it comes to data, it’s complicated because of the value of the data itself. It is important that the data is collected and contains metadata about the research process that is made available to others. It’s also time to talk about it within the academic community.

Question : The report clearly shows that the trends are multiple: the consolidation of for-profit publishing, the growth of open access publications, the fiscal pressure on university libraries and now the federal mandate. As complicated as the current situation is, it seems that MIT wants to think ahead on this issue.

Brand: I think in the publishing community, and certainly in the academic press community, we’ve been ahead of the curve on this for a while, and with some of the business models that we’ve helped implement, test and create, we find other publishers follow suit and are interested. But right now, with the new federal policy, most publishers have no choice but to start asking: What does high-quality, sustainable publishing mean if I, as a publisher, must distribute all or part of this content in open digital form?

Sharp: The goal of this report is to stimulate that conversation: more numbers, every piece of evidence. Communities are responsible for the quality of science across different disciplines, and sharing responsibility for peer review is something that motivates a lot of engagement. Maintaining this is important for discipline. Without this sustainability, scientific progress will be slower, in my opinion.