Deep within the bowels of Holborn, the archetypal keyboard-wielding shadow lurker has once again enveloped himself in comforting technology. Vince Clarke may be the synthpop genius who founded Depeche ModeYazoo and Erasurebut since giving up his spot as lead singer in Depeche to Dave Gahan in 1980, he’s been hiding behind synthesizers at the edge of the stage while colorful, charismatic singers like Alison Moyet and Andy Bell dazzle his music for him.

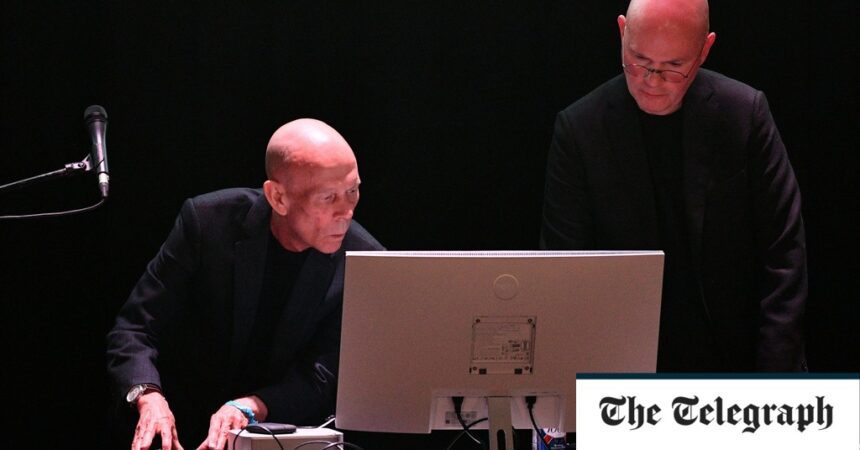

Introducing his first-ever solo album – the drone-based, avant-tronic Songs of Silence – there was nowhere to hide but inside the machine. Surrounding the basement of the London School of Economics with digital screens projecting blazing geometric fractals onto every wall, Clarke and his equally bald and dressed sidekick, Reed Hays, sequestered themselves behind a large monitor at center stage, under an attention-grabbing movie screen. “It’s weird doing this without Andy because he fills in the gaps,” Clarke said, admitting to being paralyzed in front of what often felt like a deeply immersive PowerPoint presentation.

Cathedral’s opening track was dedicated to evoking a state of timelessness: images of classic religious paintings, 1930s movie starlets and Terminators accompanied by ambient tones that gently rode cosmic waves. A fitting intro for an album born when time stood still. Clarke has been quietly “doing an Eno” (as he’s known in the business) for over a decade, leaving mainstream pop behind to create minimalist experimental electronica within VCMG (his early 2010s band with Martin Gore from Depeche) or alongside Jean-Michel. Jar. Then during confinement, YouTube tutorials on the sound possibilities of the Eurorack modular synthesizer were its Joe Wicks, and Songs of Silence its Couch to 5k.

In the performance, the visuals were as essential as the one-note soundscapes – adorned with looped Kraftwerkian kosmische (cosmic music) keys and rooted in the dark beat of Covid paranoia – themselves. Some films accentuated the theme of a song: the CGI images of Martian landscapes and crashing meteorites accompanying the sci-fi pulse of Red Planet, for example, or the game Super Mario set to the 8-bit techno sounds of Scarper.

Others have strived to draw profound human truths from these elemental sounds. White Rabbit came with an animation of a world consumed, bored, brutalized and dislocated by technology, its tribal dance coda set against images of copulating cartoon iPhones. And as Hays took to the cello to add notes of vivid melancholy to the corroded and warlike Lamentations of Jeremiah, images of deserted Eastern European corridors to the sound of distant electronic bombs evoked the horrors of the Ukrainian conflict, seen from far.

Occasional voices enhanced the proceedings. Opera singer Sarah-Jane Dale brought grace to Passage and a crackling recording of a 19th-century miner’s folk song made Blackleg sound like the ghosts of an oppressive old England returned for revenge. But Andy Bell appearing in a devil’s horn piece for an ambient rendition of Oh L’Amour would have broken the spell.

“I know it’s not a disco banger,” Clarke apologized before the spacey echo closer of Last Transmission but, sporadically, it was as transporting an experience as any pure high pop. Respect – and more than a little – due.